Yuck on a Wire

Every once in a while, the topic comes up amongst guitarists and folks who play stringed instruments: can anything useful be done with used strings?

Musicians change strings for better sound or just because we want to try something different. New strings sound crisper and clearer, offer better tone and dynamic response, play better, and have a more consistent feel up and down the instrument. The older strings get, the duller they sound, and they sometimes develop worn or corroded spots by (say) rubbing against frets or by picking up oils, skin cells, perspiration, and other grime from hands. Some players love the sound of well worn-in strings on a particular instrument, but most people agree: the newer the strings, the better the sound.

How often do players change strings? It depends on personal preference and the nature of the instrument. It's not unusual for professional guitarists to change strings before every performance; however, decent guitar strings can cost less than $5 a set, while double bass strings can cost over $100 a set. Guess which performer is more likely to consider a string change before every show?

Guitarists typically change strings every couple weeks to every few months; it depends on the player, the instrument, and the strings. Some strings have special coatings which help then resist corrosion and retain a "new" sound longer (I haven't tried many, but haven't had great luck with them); some string types just have longer lives than others. Some instruments and playing styles put greater stress on strings; some players' body chemistries corrode strings more quickly.

Personally, I almost always put on fresh strings a short while before recording, but otherwise it happens only when I notice damage or wear, dull tone bugs me, or I want to try a set which are lighter or heavier than what I'm already using. My gut feeling is that the frequency depends on how much an instrument is being played. Unlike many players, I don't like to play shows or record with brand-new strings. Strings have a bit of a break-in period where they're stretching and adjusting to pitch—the exact time varies with string design and tension—and that's when strings are most likely to break. I don't want to put on new strings right before a gig: I'd rather play a set for a day or two, make sure they're settled, then take them to a performance situation.

And, of course, sometimes strings break. There's no rule that you have to change all the strings at once, and sometimes—like the middle of a show—replacing a single broken string is a much better choice than changing them all. But with older strings this usually doesn't work: the bright tone of the brand-new string will jump out from the others in a not-so-good way.

But here's the thing: every time you change or replace strings, you've got old strings staring back at you. In most cases, they're usable, just old. What can you do with them?

In 1999, singer/songwriter Darryl Purpose and Kevin Deane started a campaign called the Second Strings Project—the idea was to collect used-but-usable sets of strings from musicians, dealers, and others and donate them to musicians in Cuba and other nations where quality strings are rare and disproportionately expensive. (Sure, guitar strings might set you back $5 here in the U.S., but in a country with an average monthly wage around $20, you see the problem.) A lot of players in these countries make due with bailing wire, shoelaces, nylon cord, re-knotted fishing line, rubber bands, and electrical wire: playable used strings from the U.S. would be a vast improvement. I have no idea if the Second String Project is still up and running—the Web site is a bit sparse—but it's a great idea. Local music shops sometimes offer similar programs: it's worth checking next time you're doing some window-shopping.

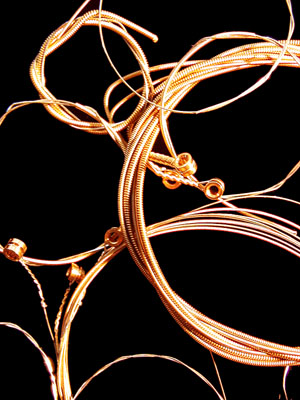

My own used strings on black velvet.

My own used strings on black velvet.Where should I start the bidding?

But here's one application for used strings I do not understand: craft jewelry. The basic idea is to wind available used strings into bracelet-sized loops, then bind them together with some silver solder. Voilà! Hip, custom jewelry—right?

Consider, for instance, former Deadhead publication Relix magazine's Wear Your Music. (Of course, the first thing I noticed about this site—besides the awful usability—is that the featured guitar is missing a string.) What is Relix doing? They're taking used strings from famous players like Carlos Santana, Les Paul, Jack Casady, Béla Fleck, Les Claypool, and Susan Tedeschi, making them into bracelets, and selling them at prices at $99 to $200 apiece.

First: if you're going to do this yourself, yes, use silver or other jewelry-safe solder and not the lead-alloy solder commonly used in electronic repair. (Solders containing lead have already been classified as a hazardous substance and banned from electronic components in the EU. Plus, you don't want lead leeching into your system.)

But, second: ewwww. Only non-musicians could find something appealing about used guitar strings. Maybe if you have an instrument tech who changes your strings every day, they aren't so grungy. But otherwise, honest: Used Strings are Yuck on a Wire. And they're only going to get worse as you wear them.

As a musician who has changed literally thousands of strings, there's no way I would want to wear them. Consider that many strings are made from materials which cause skin reactions and allergies in some people. For instance, most electric guitar and bass strings are wrapped with nickel alloys: turns out I have an allergy to nickel salts, which means I preferentially use strings wrapped with chrome or stainless steel. Wearing some nickel-wrapped guitar strings would be a quick way to big evil rashes for me. Relix makes no mention of this in their FAQ, saying that guitar strings are "typically made of steel, often coated with a nylon protective coating." Not really. Unwound metal strings are usually steel (no nylon); wound strings usually have a steel core, but can be wrapped with a variety of metals, including nickel, steel, chrome, and (for acoustic guitars) so-called bronze and phosphor bronze. Only a few of those wound acoustic strings will have any sort of coating, and it's probably damaged and wearing off.

Plus, used strings have been corroded by moisture and sweat; they've picked up oils, debris, smoke, fumes, and grime from players' hands, venues, cases, fingerboards, and the environment. Steel and nickel strings seem to emit the black funk of corrosion if you so much as breathe on them; bronze and phosphor bronze strings make your hands smell like pennies with the strum of a single chord. And wound strings contain gaps in the wrapping where sweat, sloughed-off skin cells, moisture, debris, and corroded metal live, thrive, and set up their own micro-civilizations. It ain't a happy place.

Relix says the profits from Wear Your Music go to selected charities, which I have no reason to doubt. As a fundraising enterprise for worthy organizations, maybe there's something to it.

But as functional fashion accessories? Ew.

- Categories:

- Tunings & Twangings

Hey, what's life without fine print?